“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

— Marie Curie

Of all the things to be afraid of in the world, not knowing is perhaps my biggest fear. That is why, personally, I feel that communication is extremely important. Humans are naturally inquisitive. We seek for answers, as if habitually.

If you’ve joined me in Part 1 & Part 2 of Auntie Jen’s patient journey in Radiation Therapy, you might have realised that this is an example of a “best case scenario”. As you might imagine, the real-life hospital setting poses its own set of challenges and unplanned situations that have to be managed on the fly.

So the harsh reality is that the “best case scenario” happens a lot less often that it should. In that case, how can we help patients to closer realise this?

Let me share a funny story.

I am afraid of heights whereas my husband is the opposite. Whenever we go to the theme parks, he will choose the most thrilling roller coaster rides (the ones that make you feel like you are being tumbled dry in the washing machine) and I will wiggle my way to the rides for children under 4 feet. One day, I decided to give it a shot and told him that I would do one ‘scary’ roller coaster ride with him. You should’ve seen the look of disbelief on his face!

As we climbed the steps leading to the ride and waited in line, I jokingly asked what his heart rate was before the ride. He showed me his smartwatch, with the reading close to 100 beats per minute (bpm) at rest (normal range 60 – 100 bpm). I teased him about him truly being scared of roller coasters after all.

When the ride was over, he was grinning from ear to ear and the conversation went something like this:-

Steph : Well, what is your heart rate now? Husband: 70! What's yours? Steph : ...I don't think I can even feel my legs...

Author’s Note: My heart rate was over 160+ (I might as well opt for roller coaster rides instead of my usual runs and HIIT exercises)

Magic Mountain Roller Coaster at Six Flags. Source Credit: The Coaster Views (YouTube, 2013)

I learnt something that day. The reason his heart rate was higher while in line for the ride as opposed to right after was because the stress of the entire experience was not in the actual act of riding the coaster: it was in the anticipation of it. This example lends itself well to the journey of a cancer patient.

Imagine the fear and anxiety leading up to a procedure or treatment if you were not given a heads-up for what is about to happen. Picture a situation where communication is simply nonexistent. In cancer patients, this form of emotional distress is exacerbated especially when they are already shouldering the burden of a serious disease.

Approximately 50% of cancer patients experience a form of heightened anxiety and distress prior to their radiation treatment1-2. Studies have shown that causes to such discomfort were attributed to: –

- The lack of information provided by health professionals prior to treatment planning and delivery3

- The patients’ lack of understanding of the side effects pertaining to radiation treatment3

- The inconsistency in the information provided by the care team to the patient4

- The information provided by the care team may contain medical jargon that was misconstrued by the patient and did not meet their information needs5

Why is communication – Key?

Distress in Cancer6:

A “multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social, spiritual and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms and its treatment”

Impact to the Patient

Complex medical needs and rigorous treatment regimens that oncology patients experience may be accompanied by high levels of psychosocial distress, anxiety and depression. Therefore, the impact can be manifold if healthcare professionals fail to recognize the information needs and communication preferences of patients with cancer and the consequences of not meeting these expectations.

Should these needs be left unmet, studies have shown that this may result in the cancer patient’s poorer compliance to treatment, self-care, and overall health outcomes7. Furthermore, in some cases, inadequate information and communication may lead to patients declining treatment that might otherwise improve their chance of survival8-9.

For example, Auntie Jen relies on the healthcare professionals treating her to provide her with vital information she may require to make the best healthcare decisions for herself. Avoidable failure of communication can have life-changing consequences for her.

Impact to the Care Team

Multidisciplinary teams work together collaboratively in Radiation Oncology departments in order to tailor care to patients’ needs. Typically, this team consists of Radiation Oncologists, Radiation Therapists, Radiation Oncology Nurses, and various allied healthcare professionals that communicate with the patients and have a shared responsibility over the patients’ overall patient care, education and well-being10.

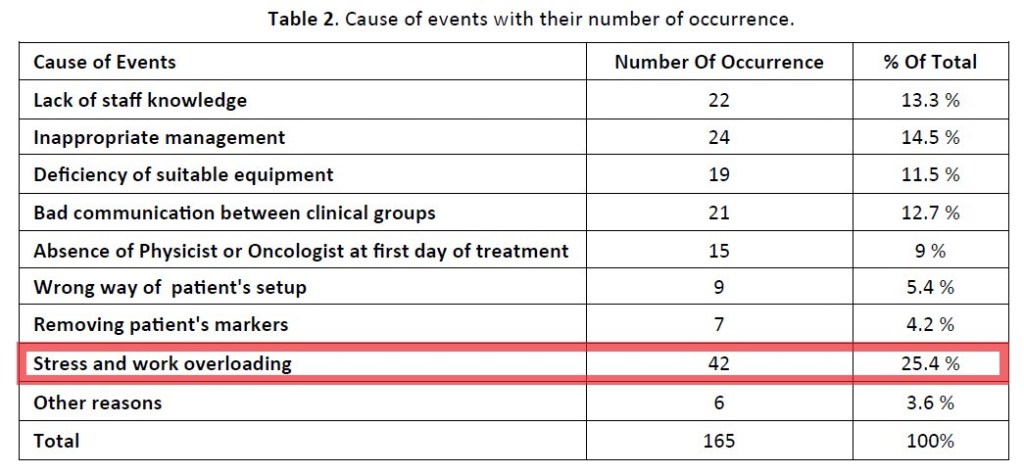

In the current day and age, as radiation treatments become more complex and sophisticated, this poses additional challenges to the care team to govern the treatment in all its details on top of the busy day-to-day grind. However, managing patients, both physically and emotionally on a daily basis also pose an additional challenge to the care team on top of the impending job stress itself.

Work-related stress is not only disruptive for the working health care individual11 but can also have a detrimental effect on the interaction with the cancer patient; especially in radiotherapy, who might be experiencing a high stress level of distress1-3. Studies have shown that physical and emotional burnout can lead to erosion of physician compassion and the quality of care physicians deliver12-13. In addition, healthcare professionals under distress are also more likely to make errors of judgement14 which may impact the aim for a seamless and error-free treatment execution in radiation therapy.

Impact to the Hospital / Institution

When a patient becomes less compliant during their radiation treatment, this may result in delays. Studies have shown that patients who are inadequately prepared for treatment and are anxious may not comply with treatment requirements and take longer to treat on a daily basis.15-16 Auntie Jen, if not given proper instructions, may neglect to show up to her treatment session with the full bladder preparation required during her radiation therapy procedure to the cervix.

As radiation treatments are usually booked on an appointment-based setting, additional time taken during a stipulated time slot may cause a backlog to the subsequent patients awaiting treatment. In radiation therapy, every treatment plan is customized to the patient, with certain disease sites requiring special adherence to preparation protocols such as patients requiring to undergo treatment with a comfortably full bladder volume and/or an empty rectum. The consequence of a delay can cause a domino effect to patients on special preparation protocols which may further impact the efficiency of the Radiation Oncology department as a whole17.

As a result of this, less patients can be treated on the machine per day and staff may be required to work longer hours to complete daily appointments17. In addition to the aforementioned, there is also the pertinent possibility that patients and/or their family members may give a negative feedback on the department’s service18.

How can we improve communication in Radiation Therapy?

Anxiety usually eases as the patient’s level of comfort and perception of safety increases –

– Elsner (2018)

and this can be facilitated by a supportive environment, trusting patient-professional relationships, sharing information, providing patient education, expressing compassion and empathy, and replacing fear of the unknown with familiarity of a daily treatment routine

Studies have shown that cancer patients want to be informed and involved in their own cancer journey19-20. A large study in the UK discovered that 87% of the 2231 patients that participated preferred to be provided with as much information as possible, be it good or bad20. Communicating this information is not only vital to the patient but also to their families and caregivers as radiation therapy is managed in an outpatient setting. This situation further necessitates good patient education as most patients and their caregivers now have to deal with treatment-related side effects at home.

Radiation Therapists as a Front-Line Communicator

Even though automation and advanced medical devices have become the standard for many medical treatments, human interaction can never be replaced.

The emerging role of Radiation Therapists (RTTs) as a front-line communicator in the radiation therapy setting has been widely discussed3,11,16. This is because RTTs communicate with their patients directly on a daily basis and they can provide daily psychosocial support to reduce patient anxiety, fear and loneliness. These relationships are important for the patient in order to help them feel comfortable and at ease.

Today – in this digital age, a wealth of technology is available or are in the midst of development to improve care. Therefore, RTTs and other allied healthcare professionals should leverage on these advancements to communicate vital information and facilitate better conversations with patients and their caregivers.

For example, mobile applications are one of the many avenues being developed in order to streamline a better patient experience in cancer care. Mobile Health apps or mHealth as termed by the World Health Organization (WHO), has been shown to improve supportive treatment for cancer patients when introduced into the clinical routine. The high acceptance rates of these apps in the surveillance and follow-up of cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy may necessitate the possibility of exploring this concept further on a much larger scale21.

In another example, Noona®, a patient care app22 designed to engage cancer patients in their care for continuous reporting and symptom monitoring has also proven to be helpful in today’s worldwide problem – the COVID-19 pandemic. In light of the new norm, non-critical radiation therapy appointments are being delayed and non-essential hospital visits deferred. The development of such platforms has allowed a quick and remote solution placed directly in the hands of the patients and their providers, without the expense of COVID-19 exposure.

Conclusion

As telemedicine and digital communication are here to stay, and are accelerating faster than ever due to the COVID-19 pandemic, both patients and healthcare professionals should continue to keep abreast and reap the full advantages of these enhanced “conveniences”.

For healthcare professionals in cancer care, the team must work closely with patients to elicit their emotional cues and understand ‘what is not being said’. By asking, acknowledging, empathizing, and providing the appropriate resources and support in a timely manner, this will make a world of difference to the patient and their families.

As for the patient? “Do not be afraid to ask.”

Patients should not let apprehension stand in the way of comprehension. They should continue to seek guidance from medical professionals and certified support groups in order to familiarize themselves with the treatment process and beyond.

Ultimately, it is vital for two-way communication in cancer care to be seamless and efficient in order to ensure treatment continuity, patient safety and enhanced satisfaction amongst patients and their treatment provider.

As you read this, there are close to 2 million new patients like Auntie Jen going through their own cancer treatment experiences. The truth is, there exists an abundance of options today that can help enhance their understanding of their present situation, with the potential repercussions of failing to do so becoming ever clearer. Let us not allow them to wander the darkness alone. Instead let us provide them with sufficient light to forge ahead to the best possible conclusions of their patient journeys.

References:

1. Holmes, N. M., & Williamson, K. (2008). A survey of cancer patients undergoing a radical course of radiotherapy to establish levels of anxiety and depression. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice, 7(2), 89-98.

2. Mitchell, D., & Lozano, R. (2012). Understanding patient psychosocial issues. Radiat Ther, 21, 96-99.

3. Halkett, G., O’Connor, M., Jefford, M., Aranda, S., Merchant, S., Spry, N., … & Schofield, P. (2018). RT Prepare: a radiation therapist-delivered intervention reduces psychological distress in women with breast cancer referred for radiotherapy. British journal of cancer, 118(12), 1549-1558.

4. Halkett, G. K., Short, M., & Kristjanson, L. J. (2009). How do radiation oncology health professionals inform breast cancer patients about the medical and technical aspects of their treatment?. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 90(1), 153-159.

5. Schnitzler, L., Smith, S. K., Shepherd, H. L., Shaw, J., Dong, S., Carpenter, D. M., … & Dhillon, H. M. (2017). Communication during radiation therapy education sessions: The role of medical jargon and emotional support in clarifying patient confusion. Patient education and counseling, 100(1), 112-120.

6. Donovan, K. A., Deshields, T. L., Corbett, C., & Riba, M. B. (2019). Update on the implementation of NCCN guidelines for distress management by NCCN member institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 17(10), 1251-1256.

7. Turner, J., Zapart, S., Pedersen, K., Rankin, N., Luxford, K., & Fletcher, J. (2005). Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 14(3), 159-173.

8. Jefford, M., & Tattersall, M. H. (2002). Informing and involving cancer patients in their own care. The lancet oncology, 3(10), 629-637.

9. Reyna, V. F., Nelson, W. L., Han, P. K., & Pignone, M. P. (2015). Decision making and cancer. American Psychologist, 70(2), 105.

10. Valentini, V., Boldrini, L., Mariani, S., & Massaccesi, M. (2020). Role of radiation oncology in modern multidisciplinary cancer treatment. Molecular oncology, 14(7), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12712

11. Elsner, K. L. (2018). Can radiation therapists detect and manage patients experiencing anxiety in the radiation oncology setting? (Master’s thesis, University of Sydney).

12. Firth-Cozens, J., & Greenhalgh, J. (1997). Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Social science & medicine, 44(7), 1017-1022.

13. Arnetz, B. B. (2001). Psychosocial challenges facing physicians of today. Social science & medicine, 52(2), 203-213.

14. Asnaashari, K., GHOLAMI, S., & Khosravi, H. R. (2014). Lessons learnt from errors in radiotherapy centers.

15. Clover, K., Oultram, S., Adams, C., Cros, L., Findlay, N., & Ponman, L. (2011). Disruption to radiation therapy sessions due to anxiety among patients receiving radiation therapy to the head and neck area can be predicted using patient self‐report measures. Psycho‐Oncology, 20(12), 1334-1341.

16. Halkett, G., O’Connor, M., Aranda, S., Jefford, M., Merchant, S., York, D., & Schofield, P. (2016). Communication skills training for radiation therapists: preparing patients for radiation therapy. Journal of medical radiation sciences, 63(4), 232-241.

17. Chan, K., Li, W., Medlam, G., Higgins, J., Bolderston, A., Yi, Q., & Wenz, J. (2010). Investigating patient wait times for daily outpatient radiotherapy appointments (a single-centre study). Journal of medical imaging and radiation sciences, 41(3), 145-151.

18. Kline, T. J. B., Willness, C., & Ghali, W. A. (2008). Predicting patient complaints in hospital settings. BMJ Quality & Safety, 17(5), 346-350.

19. Chua, G. P., Tan, H. K., & Gandhi, M. (2018). What information do cancer patients want and how well are their needs being met?. ecancermedicalscience, 12.

20. Jenkins, V., Fallowfield, L., & Saul, J. (2001). Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. British journal of cancer, 84(1), 48-51.

21. El Shafie, R. A., Weber, D., Bougatf, N., Sprave, T., Oetzel, D., Huber, P. E., … & Nicolay, N. H. (2018). Supportive care in radiotherapy based on a mobile app: prospective multicenter survey. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(8), e10916.

22. Varian. (2020). Noona | Varian. https://www.varian.com/products/software/care-management/noona